Kautilya’s Arthashastra (Read)

The second article in the series of historical antecedents of Realist IR theories will deal with the thoughts of Kautilya, an Indian philosopher and royal advisor who wrote Arthaśāstra. Kautilya served as the chief advisor to Chandragupta, the first Maurya emperor in India. He was originally a professor of economics and political science at then Takshashila University, considered as pioneer of both fields for his work of Arthaśāstra became an important precursor classical economics. The title has been translated in various ways, such as “science of politics,” or a treatise to help a king in “the acquisition and protection of the, by R.P. Kangle, “treatise on polity” by A.L. Basham, “science of material gain” by Kosambi, “science of polity” by G.P. Singh, and “science of political economy” by Roger Boesche. It discusses statecraft, economic policy, and military strategy, and is divided into fifteen books.

Roger Boesche (2003) describes Arthaśāstra as offering “wide-ranging and truly fascinating discussions on war and diplomacy.” He notes that Kautilya wishes “to have his king become a world conqueror” (Arthaśāstra Book VI Chapter I), which Boesche interprets as “conquering up to what Indians regarded as the natural borders of India, from the Himalayas all the way south to the Indian Ocean, and from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal”, excluding the land of “barbarians” or mlecchas, those outside of Indian culture (Boesche, 2003, pp. 17). Boesche also calls Kautilya a political realist who analyzed that an alliance will last only as long as it is in that ally’s as well as one’s own self-interest, in which Kautilya wrote “preference to the army or to the ally should depend on the advantages of securing the appropriate place and time for war and the expected profit” (Arthaśāstra Book VIII Chapter I).

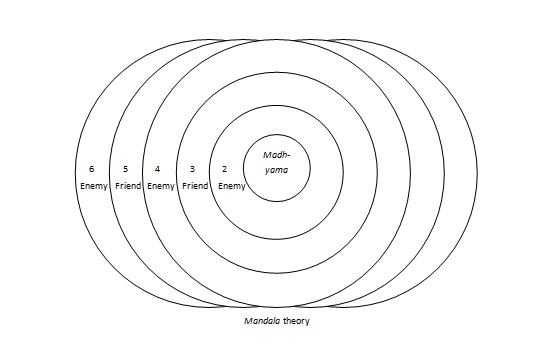

Boesche also underlines Kautilya’s analysis of which kingdoms are natural allies and which are inevitable enemies, or the so-called Mandala theory of foreign policy, in which immediate neighbors are considered as enemies, but any state on the other side of a neighboring state is regarded as an ally (“the enemy of my enemy is my friend”). In Arthaśāstra Book VI Chapter II, Kautilya wrote “The king who is situated anywhere immediately on the circumference of the conqueror's territory is termed the enemy. The king who is likewise situated close to the enemy, but separated from the conqueror only by the enemy, is termed the friend (of the conqueror).” Boesche describes the Mandala theory as follows: “Imagine a series of states to one’s west, and then number them starting with oneself. States numbered 1, 3, 5, 7, and so on will likely be friends, whereas states 2, 4, 6, 8, and so on will probably be enemies” (Boesche, 2003, pp. 18). In doing so, Boesche borrows from Arthaśāstra Book VII Chapter XVIII: “The third and the fifth states from a madhyama king are states friendly to him; while the second, the fourth, and the sixth are unfriendly. If the madhyama king shows favour to both of these states, the conqueror should be friendly with him; if he does not favour them, the conqueror should be friendly with those states.”

The second article in the series of historical antecedents of Realist IR theories will deal with the thoughts of Kautilya, an Indian philosopher and royal advisor who wrote Arthaśāstra. Kautilya served as the chief advisor to Chandragupta, the first Maurya emperor in India. He was originally a professor of economics and political science at then Takshashila University, considered as pioneer of both fields for his work of Arthaśāstra became an important precursor classical economics. The title has been translated in various ways, such as “science of politics,” or a treatise to help a king in “the acquisition and protection of the, by R.P. Kangle, “treatise on polity” by A.L. Basham, “science of material gain” by Kosambi, “science of polity” by G.P. Singh, and “science of political economy” by Roger Boesche. It discusses statecraft, economic policy, and military strategy, and is divided into fifteen books.

Roger Boesche (2003) describes Arthaśāstra as offering “wide-ranging and truly fascinating discussions on war and diplomacy.” He notes that Kautilya wishes “to have his king become a world conqueror” (Arthaśāstra Book VI Chapter I), which Boesche interprets as “conquering up to what Indians regarded as the natural borders of India, from the Himalayas all the way south to the Indian Ocean, and from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal”, excluding the land of “barbarians” or mlecchas, those outside of Indian culture (Boesche, 2003, pp. 17). Boesche also calls Kautilya a political realist who analyzed that an alliance will last only as long as it is in that ally’s as well as one’s own self-interest, in which Kautilya wrote “preference to the army or to the ally should depend on the advantages of securing the appropriate place and time for war and the expected profit” (Arthaśāstra Book VIII Chapter I).

Boesche also underlines Kautilya’s analysis of which kingdoms are natural allies and which are inevitable enemies, or the so-called Mandala theory of foreign policy, in which immediate neighbors are considered as enemies, but any state on the other side of a neighboring state is regarded as an ally (“the enemy of my enemy is my friend”). In Arthaśāstra Book VI Chapter II, Kautilya wrote “The king who is situated anywhere immediately on the circumference of the conqueror's territory is termed the enemy. The king who is likewise situated close to the enemy, but separated from the conqueror only by the enemy, is termed the friend (of the conqueror).” Boesche describes the Mandala theory as follows: “Imagine a series of states to one’s west, and then number them starting with oneself. States numbered 1, 3, 5, 7, and so on will likely be friends, whereas states 2, 4, 6, 8, and so on will probably be enemies” (Boesche, 2003, pp. 18). In doing so, Boesche borrows from Arthaśāstra Book VII Chapter XVIII: “The third and the fifth states from a madhyama king are states friendly to him; while the second, the fourth, and the sixth are unfriendly. If the madhyama king shows favour to both of these states, the conqueror should be friendly with him; if he does not favour them, the conqueror should be friendly with those states.”

Boesche notes that Kautilya was willing to make treaties he knew he would break, as Kautilya wrote in Arthaśāstra Book VII Chapter XIV: “When the conqueror is thus attacked by the combined army of his enemies, he may tell their leader: ‘I shall make peace with you’ … The combination being broken, he may set the leader against the weak among his enemies.” Boesche concludes that “Because a king abides by a treaty only for so long as it is advantageous, Kautilya regarded all allies as future conquests when the time is ripe” (Boesche, 2003, pp. 21).

Kautilya’s concept of war and peace is divided into five forms of peace and three forms of war (Arthaśāstra Book VII Chapter VI):

Kautilya proposed that a king with a strong army may undertake an open fight, otherwise he should fight a treacherous battle (Arthaśāstra Book X Chapter III). Boesche takes note of Kautilya's doctrine of silent war or a war of assassination against an unsuspecting king and his approval of secret agents who killed enemy leaders and sowed discord among them (Boesche, 2003, pp. 23).

Kautilya also viewed women as weapons of war, using women against the enemy by "exhibiting women endowed with bewitching youth and beauty" then "by causing the woman to go to another person or by pretending that another person has violently carried her off, they may bring about quarrel among those who love that woman" (Arthaśāstra Book XI Chapter I).

Kautilya’s Arthaśāstra Influence to Realism

Kautilya is regarded as the first great political realist because of his harsh pragmatism in the Arthaśāstra, in which he found no questions as immoral: he was willing to make break treaties he made, he preached of silent war or a war of assassination against an unsuspecting king, he approved of secret agents who killed enemy leaders and sowed discord among them. His Arthaśāstra was also a book of political realism, in which he analyzed how the political world did work and not very often stating how it ought to work. Kautilya argued that in the world of international politics (combination of states), it was natural that nations interact with each other with "means of sowing the seeds of dissension; and in the case of the powerful, it is by means of coercion" (Arthaśāstra Book IX Chapter VII), reflecting a political realist's argument that there will always be conflict in international relations and, in effect, the strongest state will rule. Kautilya also provided a realist's assumption that every nation acts to maximize power and self-interest, and therefore moral principles or obligations have little or no force in actions among nations ("preference to the army or to the ally should depend on the advantages of securing the appropriate place and time for war and the expected profit," Arthaśāstra Book VIII Chapter I).

Kautilya's view continued Thucydides' History a century after, who regarded the request for negotiation as a sign of weakness (see the Melian Dialogue). Unless a nation forced to rely on the kindnes of neighboring states can change rapidly, it is doomed to destruction ("When a king of inferior power ... request a third king of superior power, ... If the king to whom this proposal is made is powerful enough to retaliate, he may declare war; but otherwise he may accept the proposal", Arthaśāstra Book VII Chapter VII). In the same way as Thucydides', Kautilya demonstrated the ineffectiveness of moral pleas when confronted by a superior power.

Kautilya's Arthaśāstra has also been compared to Machiavelli's Il Principe of later antiquity: Max Weber in Politics as a Vocation (1919) observed, "Truly radical 'Machiavellianism', in the popular sense of that word, is classically expressed in Indian literature in the Arthasastra of Kautilya (written long before the birth of Christ, ostensibly in the time of Chandragupta [Maurya]): compared to it, Machiavelli’s The Prince is harmless" (quoted in Boesche, 2003, pp. 1).

Kautilya's emphasis on the dissensions in the combination of states predates the Realist's assumption that the international system is anarchic, forcing states to arrive at relations with superior power, rather than requesting for negotiation. Kautilya confirmed that states tend to pursue self-interest, even alliances and treaties shall break on the consideration of advantages and profit.

Kautilya’s concept of war and peace is divided into five forms of peace and three forms of war (Arthaśāstra Book VII Chapter VI):

- Peace with no definite terms (aparipanita): an agreement of peace with no terms of time, space, or work with an enemy made merely for mutual peace;

- Peace with no specific end (akritachikírshá): an agreement of peace in which the rights of equal, inferior, and superior powers concerned in the agreement are defined according to their respective positions;

- Peace with binding terms (kritasleshana): an agreement of peace kept secure whose terms are invariably observed and strictly maintained so that no dissension may creep among the parties;

- The breaking of peace (kritavidúshana): a broken agreement of peace;

- Restoration of peace broken (apasírnakriyá): a reconciliation made with a servant, or a friend, or any other renegade.

- Open battle: a battle fought in daylight and in some locality;

- Treacherous battle;

- Silent battle: the killing of an enemy by employing spies when there is no talk of battle at all.

Kautilya proposed that a king with a strong army may undertake an open fight, otherwise he should fight a treacherous battle (Arthaśāstra Book X Chapter III). Boesche takes note of Kautilya's doctrine of silent war or a war of assassination against an unsuspecting king and his approval of secret agents who killed enemy leaders and sowed discord among them (Boesche, 2003, pp. 23).

Kautilya also viewed women as weapons of war, using women against the enemy by "exhibiting women endowed with bewitching youth and beauty" then "by causing the woman to go to another person or by pretending that another person has violently carried her off, they may bring about quarrel among those who love that woman" (Arthaśāstra Book XI Chapter I).

Kautilya’s Arthaśāstra Influence to Realism

Kautilya is regarded as the first great political realist because of his harsh pragmatism in the Arthaśāstra, in which he found no questions as immoral: he was willing to make break treaties he made, he preached of silent war or a war of assassination against an unsuspecting king, he approved of secret agents who killed enemy leaders and sowed discord among them. His Arthaśāstra was also a book of political realism, in which he analyzed how the political world did work and not very often stating how it ought to work. Kautilya argued that in the world of international politics (combination of states), it was natural that nations interact with each other with "means of sowing the seeds of dissension; and in the case of the powerful, it is by means of coercion" (Arthaśāstra Book IX Chapter VII), reflecting a political realist's argument that there will always be conflict in international relations and, in effect, the strongest state will rule. Kautilya also provided a realist's assumption that every nation acts to maximize power and self-interest, and therefore moral principles or obligations have little or no force in actions among nations ("preference to the army or to the ally should depend on the advantages of securing the appropriate place and time for war and the expected profit," Arthaśāstra Book VIII Chapter I).

Kautilya's view continued Thucydides' History a century after, who regarded the request for negotiation as a sign of weakness (see the Melian Dialogue). Unless a nation forced to rely on the kindnes of neighboring states can change rapidly, it is doomed to destruction ("When a king of inferior power ... request a third king of superior power, ... If the king to whom this proposal is made is powerful enough to retaliate, he may declare war; but otherwise he may accept the proposal", Arthaśāstra Book VII Chapter VII). In the same way as Thucydides', Kautilya demonstrated the ineffectiveness of moral pleas when confronted by a superior power.

Kautilya's Arthaśāstra has also been compared to Machiavelli's Il Principe of later antiquity: Max Weber in Politics as a Vocation (1919) observed, "Truly radical 'Machiavellianism', in the popular sense of that word, is classically expressed in Indian literature in the Arthasastra of Kautilya (written long before the birth of Christ, ostensibly in the time of Chandragupta [Maurya]): compared to it, Machiavelli’s The Prince is harmless" (quoted in Boesche, 2003, pp. 1).

Kautilya's emphasis on the dissensions in the combination of states predates the Realist's assumption that the international system is anarchic, forcing states to arrive at relations with superior power, rather than requesting for negotiation. Kautilya confirmed that states tend to pursue self-interest, even alliances and treaties shall break on the consideration of advantages and profit.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed