English Civil Unrest Put into Context

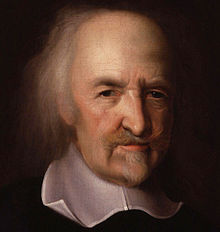

"My mother gave birth to twins: myself and fear," Hobbes reported, commenting on his premature birth on 5 April 1588 in Malmesbury, England, when his mother heard of the coming invasion of the Spanish Armada, a fleet of Spanish warships.[1] Hobbes had been born in the midst of Anglo-Spanish War (1585-1604), and he lived in a period of civil unrest leading to the English Civil War (1642-1651), leading him later to emphasize the determining power of fear more than any other philosopher. He even proposed that a political community be oriented around the fear of violent death, which he dubbed the greatest evil (summum malum). His emphasis on fear bears resemblance with previous Realist writers; even one of Hobbes’ first scholarly works was a translation of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian Wars in 1629, of which Hobbes said that he offered the translation as a reminder that the ancients believed democracy (rule by the people) to be the least effective form of government.

Hobbes’ Leviathan (Read)

The book Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil (to be referred as Leviathan from this point forward for convenience) was published in 1651. Leviathan concerns the structure of society and legitimate government, which uses “social contract theory” (theory that typically addresses the questions of the origin of society and the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual) to conclude that we ought to submit to the authority of an absolute—undivided and unlimited—sovereign power. In the book, Hobbes wrote that civil war and the brute situation of a state of nature, which was "the war of all against all", could only be avoided by strong undivided government.[2]

Leviathan is divided into four main parts: Of Man, Of Commonwealth, Of a Christian Commonwealth, and Of the Kingdom of Darkness. Of Man takes account of human nature, explaining humanity in a materialistic way, and denies incorporeal body and substance. It also rejects finis ultimus (utmost aim) and summum bonum (greatest good) as previous thought had spoken of. Hobbes spoke of a summum malum (greatest evil), which was the danger of violent death. In the nature of man, Hobbes found three principal causes of quarrel: competition, diffidence, and glory. “The first maketh men invade for gain; the second, for safety; and the third, for reputation” (Leviathan Chapter XIII). Because the condition of man “is a condition of war of every one against every one, in which case every one is governed by his own reason, and there is nothing he can make use of that may not be a help unto him in preserving his life against his enemies,” Hobbes pointed out a number of laws of nature: first, “to seek peace and follow it”; and second, “by all means we can to defend ourselves” (Chapter XIV). What Hobbes suggested by that reason was to seek peace; however if peace could not be had, to use all of the advantages of war. He also suggested to renounce one's right to all things if others were willing to do the same, to quit the state of nature, and to enter covenants by fear with the authority to command them in all things. Hobbes concluded Of Man by articulating additional seventeen laws of nature in Chapter XV.

Of Commonwealth explains the purpose of a commonwealth, which is to restraint upon men to prevent consequent condition of war when there is no visible power to keep them and to tie them by fear of punishment to the performance of their covenants. The commonwealth is instituted when all agree in the following manner: “I authorise and give up my right of governing myself to this man, or to this assembly of men, on this condition; that thou give up, thy right to him, and authorise all his actions in like manner” (Chapter XVII).

The rights of the sovereigns are as given in Chapter XVIII:

Analysis of Leviathan; Its Influence to Realism

Hobbes’ Leviathan shared the Realist perspective that humankind is not inherently benevolent but rather self-centered and competitive; in which human nature viewed as egocentric and conflicting (“the condition of man is a condition of war of every one against every one”) unless there exist conditions under which humans may coexist (“to enter covenants of commonwealth”). Such state of nature equals to the anarchy in international system. Leviathan thus provided a basis for the Realist understanding of international relations. Hans Morgenthau (1967, p. 113) credited Hobbes’ conception of international relations as providing the “stock of trade” of the discipline, while Michael Smith (1986, p. 13) praised that Hobbes’ “analysis of the state of nature remains the defining feature of Realist thought. His notion of the international state of nature as a state of war is shared by virtually everyone calling himself a Realist.” Charles W. Kegley and Eugene Wittkopf (1995, p.22) assured that the “recent realist thinking derives especially from the political philosophies of the Italian theorist Niccolo Machiavelli and the English theoretician Thomas Hobbes.” R. N. Berki (1981, p. 142) argued that there was continuity in “the tradition of Realpolitik from Machiavelli and Hobbes to Thompson and Morgenthau,” while Martin Wight (1991, p. 6-7) found the basic arguments of Hobbes’ Leviathan and E. H. Carr’s Twenty Years’ Crisis to be the same.

To understand how Hobbes fits the definition of Realism, we can see Jack Donnelly (2000, p. 14), who wrote that, in the natural condition of man that is a state of war, Hobbes demonstrated natural equality in typically “Realist” fashion: even “the weakest has strength enough to kill the strongest, either by secret machination or by confederacy with others” (in Leviathan Chapter XIII). Donnelly (2000, p. 14) maintained that, “If some were much more powerful than others, social order might be forcibly imposed. Rough equality of capabilities, however, makes this anarchic world one of inescapable and universal danger.”

Donnelly commented on Hobbes’ three principal causes of quarrel: “for Hobbes… competition, diffidence, and glory may be controlled by superior power… But they cannot be eliminated.” Thus Donnelly maintained that the task of politics was to replace anarchic equality with hierarchical political authority. However, Donnelly argued that international relations remained a domain of anarchy, a state of war. “Barring world government, there is no escape from this state of war.” (ibid., p. 15)

A Reconsideration of Realism in Hobbes’ Leviathan

Despite the depictions of Hobbes as a theorist of Realism as this article previously mentioned, several writers argued that Hobbes might not be as close to a Realist understanding of international relations as has been prevalently held. A. Nuri˙ Yurdusev (2006) argued that given Hobbes’s conception of man and the state of nature, the formation of Leviathan and the law of nature, Hobbes gave us a perception of international relations which was not always conflicting and comprised the adjustments of conflicting interests, leading to the possibility of alliances and cooperation in international relations. Hobbes did not suggest the establishment of a world/international Leviathan because “while the interpersonal state of nature is unbearable, the international state of nature is bearable. In the interpersonal state of nature man has no culture, no industry, no art, no navigation, no civilisation and his life is poor, solitary, nasty and brutish. But, in the international state of nature as the states uphold the industry of their subjects, then, individuals do not have the misery that they experience in the interpersonal state of nature” (p. 315).

Theodore Christov (2009) saw that Hobbes’ depiction of voluntary alliances at the level of natural man situated him not as a theorist of lawlessness and anarchy but as a proponent of a highly complex dynamic of social cooperation and partnership. Christov argued that the international state of nature, analogous to group alliances in pre-civil condition, follows principles of cooperation effectively constraining states’ behavior. The Hobbesian international political order is, at its core, concerned with both security and well-being in a continual improvement of the international system.

Hobbes might have not been the theorist of international anarchy as Realists had been suggesting him to be, but his Leviathan work had been a reader in Realist IR theories for its contribution to the concept of international anarchy.

Bibliography

[1] “Thomas Hobbes Biography”, URL= http://www.notablebiographies.com/He-Ho/Hobbes-Thomas.html

[2] Lloyd, Sharon A. and Sreedhar, Susanne, "Hobbes's Moral and Political Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2013/entries/hobbes-moral/

"My mother gave birth to twins: myself and fear," Hobbes reported, commenting on his premature birth on 5 April 1588 in Malmesbury, England, when his mother heard of the coming invasion of the Spanish Armada, a fleet of Spanish warships.[1] Hobbes had been born in the midst of Anglo-Spanish War (1585-1604), and he lived in a period of civil unrest leading to the English Civil War (1642-1651), leading him later to emphasize the determining power of fear more than any other philosopher. He even proposed that a political community be oriented around the fear of violent death, which he dubbed the greatest evil (summum malum). His emphasis on fear bears resemblance with previous Realist writers; even one of Hobbes’ first scholarly works was a translation of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian Wars in 1629, of which Hobbes said that he offered the translation as a reminder that the ancients believed democracy (rule by the people) to be the least effective form of government.

Hobbes’ Leviathan (Read)

The book Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil (to be referred as Leviathan from this point forward for convenience) was published in 1651. Leviathan concerns the structure of society and legitimate government, which uses “social contract theory” (theory that typically addresses the questions of the origin of society and the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual) to conclude that we ought to submit to the authority of an absolute—undivided and unlimited—sovereign power. In the book, Hobbes wrote that civil war and the brute situation of a state of nature, which was "the war of all against all", could only be avoided by strong undivided government.[2]

Leviathan is divided into four main parts: Of Man, Of Commonwealth, Of a Christian Commonwealth, and Of the Kingdom of Darkness. Of Man takes account of human nature, explaining humanity in a materialistic way, and denies incorporeal body and substance. It also rejects finis ultimus (utmost aim) and summum bonum (greatest good) as previous thought had spoken of. Hobbes spoke of a summum malum (greatest evil), which was the danger of violent death. In the nature of man, Hobbes found three principal causes of quarrel: competition, diffidence, and glory. “The first maketh men invade for gain; the second, for safety; and the third, for reputation” (Leviathan Chapter XIII). Because the condition of man “is a condition of war of every one against every one, in which case every one is governed by his own reason, and there is nothing he can make use of that may not be a help unto him in preserving his life against his enemies,” Hobbes pointed out a number of laws of nature: first, “to seek peace and follow it”; and second, “by all means we can to defend ourselves” (Chapter XIV). What Hobbes suggested by that reason was to seek peace; however if peace could not be had, to use all of the advantages of war. He also suggested to renounce one's right to all things if others were willing to do the same, to quit the state of nature, and to enter covenants by fear with the authority to command them in all things. Hobbes concluded Of Man by articulating additional seventeen laws of nature in Chapter XV.

Of Commonwealth explains the purpose of a commonwealth, which is to restraint upon men to prevent consequent condition of war when there is no visible power to keep them and to tie them by fear of punishment to the performance of their covenants. The commonwealth is instituted when all agree in the following manner: “I authorise and give up my right of governing myself to this man, or to this assembly of men, on this condition; that thou give up, thy right to him, and authorise all his actions in like manner” (Chapter XVII).

The rights of the sovereigns are as given in Chapter XVIII:

- The subjects cannot lawfully make a new covenant amongst themselves to be obedient to any other, in anything whatsoever, without permission from the sovereign (meaning the subjects cannot lawfully change the form of government).

- Because the covenant forming the commonwealth results from subjects giving to the sovereign the right to act for them, the sovereign cannot breach the covenant; and consequently the subjects cannot be freed from the covenant.

- The sovereign exists because the majority has consent their voice; the minority must consent with the rest and be contented to avow all the actions of the sovereign.

- Every subject by this institution is author of all the actions and judgments of the sovereign: hence the sovereign cannot injure any of his subjects and cannot be accused of injustice.

- Consequently, the sovereign cannot justly be put to death by the subjects.

- Because the end of this institution is peace and defense of the subjects, the sovereign has the right to judge the means of peace and defense, to do whatever he thinks necessary for the preserving of peace and security, by prevention of discord at home and hostility from abroad. Therefore, the sovereign may judge what opinions and doctrines are averse, who are to be trusted to speak to multitudes of people, and who shall examine the doctrines of all books before they are published.

- The sovereign may prescribe the rules of propriety (or meum and tuum) and civil law.

- The sovereign has the right of judicature in all cases.

- The sovereign has the right of making war and peace for the public good and to assemble, arm, and pay the forces.

- The sovereign may choose all counselors, ministers, magistrates, and officers, both in peace and war.

- The sovereign may reward with riches or honor, and to punish with corporal or pecuniary (monetary) punishment or ignominy (disgrace).

- The sovereign may establish laws of honor and a public rate of worth.

Analysis of Leviathan; Its Influence to Realism

Hobbes’ Leviathan shared the Realist perspective that humankind is not inherently benevolent but rather self-centered and competitive; in which human nature viewed as egocentric and conflicting (“the condition of man is a condition of war of every one against every one”) unless there exist conditions under which humans may coexist (“to enter covenants of commonwealth”). Such state of nature equals to the anarchy in international system. Leviathan thus provided a basis for the Realist understanding of international relations. Hans Morgenthau (1967, p. 113) credited Hobbes’ conception of international relations as providing the “stock of trade” of the discipline, while Michael Smith (1986, p. 13) praised that Hobbes’ “analysis of the state of nature remains the defining feature of Realist thought. His notion of the international state of nature as a state of war is shared by virtually everyone calling himself a Realist.” Charles W. Kegley and Eugene Wittkopf (1995, p.22) assured that the “recent realist thinking derives especially from the political philosophies of the Italian theorist Niccolo Machiavelli and the English theoretician Thomas Hobbes.” R. N. Berki (1981, p. 142) argued that there was continuity in “the tradition of Realpolitik from Machiavelli and Hobbes to Thompson and Morgenthau,” while Martin Wight (1991, p. 6-7) found the basic arguments of Hobbes’ Leviathan and E. H. Carr’s Twenty Years’ Crisis to be the same.

To understand how Hobbes fits the definition of Realism, we can see Jack Donnelly (2000, p. 14), who wrote that, in the natural condition of man that is a state of war, Hobbes demonstrated natural equality in typically “Realist” fashion: even “the weakest has strength enough to kill the strongest, either by secret machination or by confederacy with others” (in Leviathan Chapter XIII). Donnelly (2000, p. 14) maintained that, “If some were much more powerful than others, social order might be forcibly imposed. Rough equality of capabilities, however, makes this anarchic world one of inescapable and universal danger.”

Donnelly commented on Hobbes’ three principal causes of quarrel: “for Hobbes… competition, diffidence, and glory may be controlled by superior power… But they cannot be eliminated.” Thus Donnelly maintained that the task of politics was to replace anarchic equality with hierarchical political authority. However, Donnelly argued that international relations remained a domain of anarchy, a state of war. “Barring world government, there is no escape from this state of war.” (ibid., p. 15)

A Reconsideration of Realism in Hobbes’ Leviathan

Despite the depictions of Hobbes as a theorist of Realism as this article previously mentioned, several writers argued that Hobbes might not be as close to a Realist understanding of international relations as has been prevalently held. A. Nuri˙ Yurdusev (2006) argued that given Hobbes’s conception of man and the state of nature, the formation of Leviathan and the law of nature, Hobbes gave us a perception of international relations which was not always conflicting and comprised the adjustments of conflicting interests, leading to the possibility of alliances and cooperation in international relations. Hobbes did not suggest the establishment of a world/international Leviathan because “while the interpersonal state of nature is unbearable, the international state of nature is bearable. In the interpersonal state of nature man has no culture, no industry, no art, no navigation, no civilisation and his life is poor, solitary, nasty and brutish. But, in the international state of nature as the states uphold the industry of their subjects, then, individuals do not have the misery that they experience in the interpersonal state of nature” (p. 315).

Theodore Christov (2009) saw that Hobbes’ depiction of voluntary alliances at the level of natural man situated him not as a theorist of lawlessness and anarchy but as a proponent of a highly complex dynamic of social cooperation and partnership. Christov argued that the international state of nature, analogous to group alliances in pre-civil condition, follows principles of cooperation effectively constraining states’ behavior. The Hobbesian international political order is, at its core, concerned with both security and well-being in a continual improvement of the international system.

Hobbes might have not been the theorist of international anarchy as Realists had been suggesting him to be, but his Leviathan work had been a reader in Realist IR theories for its contribution to the concept of international anarchy.

Bibliography

- Berki, R. N. (1981) On Political Realism. London: J. M. Dent and Sons.

- Christov, Theodore (2009) “Beyond International Anarchy: Thomas Hobbes on the Laws of Nations.” Draft for presentation at the University of Chicago Political Theory Workshop, 13 April 2009.

- Donnelly, Jack (2000) Realism and International Relations. Cambridge University Press.

- Hobbes, Thomas (1651) Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil. Chapter XIII: Of the Natural Condition of Mankind as Concerning Their Felicity and Misery.

- ___ (1651) Leviathan. Chapter XIV: Of the First and Second Natural Laws, and of Contracts.

- ___ (1651) Leviathan. Chapter XV: Of Other Laws of Nature.

- ___ (1651) Leviathan. Chapter XVII: Of the Causes, Generation, and Definition of a Commonwealth.

- ___ (1651) Leviathan. Chapter XVIII: Of the Rights of Sovereigns by Institution.

- Kegley, Charles W. and Eugene R. Wittkopf (1995) World Politics: Trend and Transformation, 5th ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Lloyd, Sharon A. and Sreedhar, Susanne. (2013) "Hobbes's Moral and Political Philosophy," The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2013/entries/hobbes-moral/

- Morgenthau, Hans (1967) Scientific Man Versus Power Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Smith, Michael J. (1986) Realist Thought from Weber to Kissinger. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Wight, Martin (1991) International Theory: The Three Traditions, ed. by Brian Porter and Gabriele Wight. Leicester: Leicester University Press.

- Yurdusev, A. Nuri˙ (2006) “Thomas Hobbes and International Relations: from Realism to Rationalism.” Australian Journal of International Affairs Vol. 60, No. 2, p. 305-321, June 2006.

[1] “Thomas Hobbes Biography”, URL= http://www.notablebiographies.com/He-Ho/Hobbes-Thomas.html

[2] Lloyd, Sharon A. and Sreedhar, Susanne, "Hobbes's Moral and Political Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2013/entries/hobbes-moral/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed